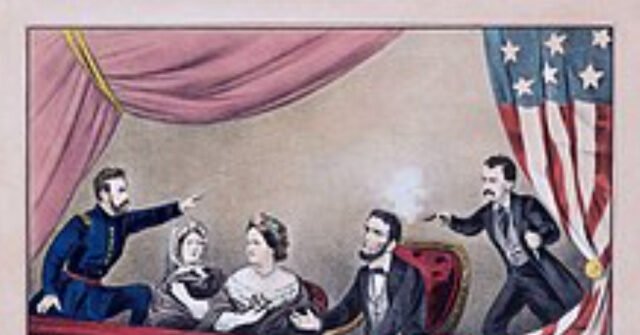

The familiar story of Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was that he was a lone mad gunman who operated with a small group of conspirators loyal to him. The true story, much of it detailed for the first time in the new bestselling book, The Unvanquished, is much darker and involves a well-planned, well-funded, and well-organized shadowy group composed of scores of individuals with direct ties to the government of the Confederate States of America: the Confederate Secret Service.

This article reveals the opening chapter of a complex plot to kidnap Lincoln. The operation was part of a more extensive campaign by the Secret Service to use novel unconventional warfare enabling the Confederacy to survive the war. As in most insurgencies, the South did not have to win the war—just survive it.

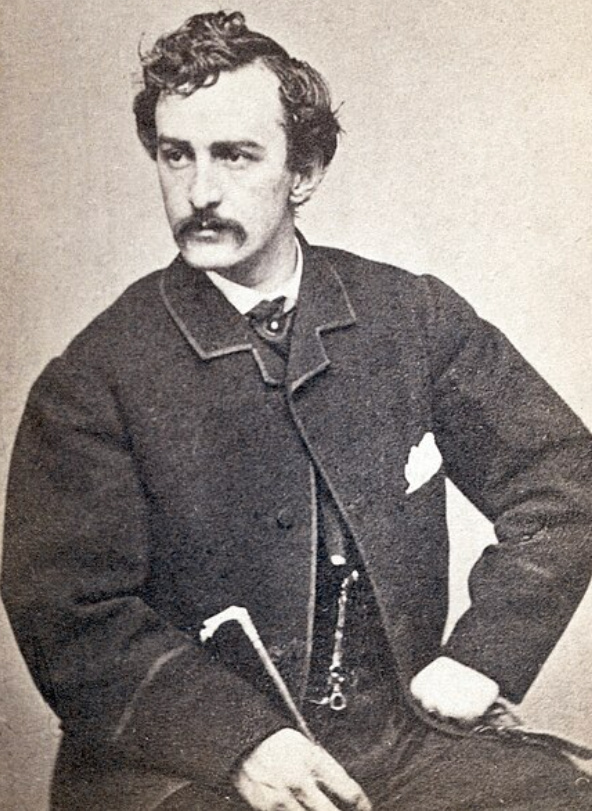

Far from a crazed madman, Booth was a handsome, popular 26-year-old actor known for his keen mind and charismatic personality. On October 18, 1864, he traveled to Canada under an absurd pretext: to enhance his theatrical wardrobe. Instead, he checked into Room 150 of the unofficial northern headquarters for the Confederate Secret Service, the St. Lawrence Hall Hotel in Montreal, and plotted with other Confederate agents. Booth’s presence part of a larger campaign of irregular warfare that included election interference, press influence operations, an insurrection, and—a campaign of political influence and terror and that would be unleashed on the North.

The Confederate Secret Service, a dynamic but unofficial agency of the Confederate government, was created overnight and staffed by a relatively small number of extraordinary individuals. Decades ahead of their time, the shadow warriors specialized in everything from novel spy gadgets, such as timebombs, to election influence operations. They helped write the campaign platform for the Copperhead-dominated Democratic Party in 1864 (putting an end to the war through an armistice). Much of the organization remains cloaked in secrecy because its files and records were deliberately burned in the war’s final days.

Confederate Secret Service political operative George Nicholas Sanders checked into the St. Lawrence Hall one day later on October 19, in Room 169 just down the hall from Booth. Sanders advocated for the “Theory of the Dagger” and ran in circles in Europe before the war that justified tyrannicide. Three credible eyewitnesses saw the two men together—Wilkes, “the handsomest man in America” and fat, restless, piratical Sanders always taking “furious, incessant whiffs” from his cigar. “They were talking confidentially, and drinking together. I saw them go into Dowley’s [hotel bar] and have a drink together,” recalled one man under oath.

After meeting Sanders, Booth made his way to the billiards room next to Dooley’s Bar. The bar catered to Confederates and served mint julips year-round. Politics swirled in the air, and Booth is said to have exclaimed, “It made d—d little difference [who was elected], head or tail—Abe’s contract was near up, and whether elected or not, he would get his goose cooked.” Later, Booth boasted, “Do you know I have the sharpest play laid out ever done in America? I can bag the biggest game this side of —. You’ll hear of a double carom one of these days.”

Only the day before the meeting, an example of the many creative clandestine activities of the Confederate Secret Service designed to injure the Northern cause, Confederate saboteurs had crossed the border to raid the town of St. Albans, Vermont. They held up three banks, making off with over $200,000. The raid was designed to create an incident that would draw the British, who had Southern sympathies, into the war on the side of the Confederacy. Confederates also hoped it would force the Union to place more troops on the northern border to guard against future raids. The raiders almost caused an international incident when a local posse of Northern townspeople pursued them as they fled back to Canada. Instead, Canadian authorities rounded up approximately a dozen prisoners and recovered and returned over $80,000 of the stolen money. From Canada, the Confederate Secret Service unleashed even bolder operations, such as plans to burn New York City to the ground and even a crude campaign of biological warfare.

According to St. Lawrence Hall’s guest book, another crucial Confederate Secret Service operative checked in during Booth’s stay: John Harrison Surratt, who would emerge as an essential member of Booth’s team and one of the South’s most significant operators. The 23-year-old divinity student-turned-Confederate spy frequently stayed at the hotel. The guest and arrival books have entries under his name and various aliases more than a dozen times. Upon his father’s death, he assumed the role of postmaster and innkeeper of Surratt’s Tavern in Clinton, Maryland. His mother, Mary, had a boarding house in Washington, DC. Both destinations were safe houses for the Confederate Secret Service.

“The French Woman,” spy vixen Sarah Antoinette Slater, often accompanied Surratt. The black-eyed, fair-complexioned, slim twentysomething got bored sitting around waiting for her husband to return from the war, so she volunteered for Secret Service work. She was tied to some of their most critical missions. For instance, months later, Slater aided the St. Albans raiders who Canadian authorities had rounded up. Often wearing a veil and speaking perfect French, she covertly carried papers from Richmond stating the men were not criminals but agents acting on behalf of their government, which halted their extradition to the United States.

Booth’s diary entries reveal the Confederate Secret Service’s plans. “For six months we had worked to capture [Lincoln],” Booth wrote in early April 1865, placing the origins of scheme to his October visit to Montreal. He also explained the advantages of a plot to capture versus kill: the president could be used as political leverage in negotiations, and seizing the leader of the Union could destabilize Federal operations and war plans.

The larger story is told in my new bestselling book, The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations. The book reveals the drama of irregular guerrilla warfare that altered the course of the Civil War, including the story of Lincoln’s special forces who donned Confederate gray to hunt Mosby and his Confederate Rangers from 1863 to the war’s end at Appomattox—a previously untold story that inspired the creation of U.S. modern special operations in World War II as well as the full story of the Confederate Secret Service including its ties to John Wilkes Booth and involvement in Lincoln’s assassination.

John Singleton Mosby and his Rangers were called in to help coordinate with potential Confederate kidnappers, including preacher spy Captain Thomas Nelson Conrad, to determine and protect egress routes from Washington to Richmond. At Lafayette Park, “only a stone’s throw from the White House,” Conrad observed: “Officials’ ingress and egress, noting about what hours of the day he might venture forth, size of the accompanying escort if any: and all other details. . . . We had to determine at what point it would be most expedient to capture the carriage and take possession of Mr. Lincoln; and then whether to move with him through Maryland to the lower Potomac and cross or the upper Potomac and deliver the prisoner to Mosby’s Confederacy for transportation to Richmond. To secure the points necessary for reaching a proper conclusion about all these things required days of careful work and observation. . . . Having scouted the country pretty thoroughly . . . we finally concluded to take the lower Potomac route.”

After the assassination, Booth would take the same route to escape from Washington and into Virginia. The path involved assistance from Southern operative Dr. Samuel Mudd in moving from Washington through southern Maryland using covert lines established by the Confederate Secret Service. The book provides deep research, original source documents, and sworn testimony that give evidence of these connections and a new perspective on the Civil War.

When the assassination option was introduced is not known, but the evidence for Confederate ties to John Wilkes Booth is undeniable. Later, George Sanders proclaimed to a London-based Daily Telegraph correspondent that the Confederate Secret Service would conduct covert missions that “would make the world shudder.”

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically-acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of thirteen books, including his new bestselling book on the Civil War The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations, currently in the front display of Barnes and Noble stores nationwide. His latest in-person and virtual, free–to–attend event on September 18 is at The International Spy Museum. O’Donnell’s other bestsellers include: The Indispensables, The Unknowns, and Washington’s Immortals. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and often speaks on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickKODonnell.com @combathistorian