Getty Images

Getty ImagesJoyce Davies was eight when her father died in a factory fire.

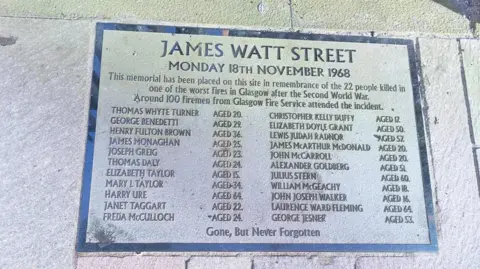

On 18 November 1968, a blaze broke out at the Stern furniture factory on James Watt Street in Glasgow.

The stairs were made of wood. There were bars across the windows. The fire alarm had been disconnected for six months.

Workers tried to escape the flames but the fire door leading to the street had been padlocked, a measure aimed at preventing thefts.

Trapped inside the building, screaming for help, 22 people died.

Among the deaths was Henry Fulton Brown. He was 36 at the time of his death.

Other than his voice, and that he made her feel “safe and secure”, Joyce doesn’t remember much more about her father. Her traumatised mother removed all evidence of him from their home, and although she lived into her eighties, never spoke of him again.

Two years earlier, 116 children and 28 adults had been killed when thousands of tonnes of coal waste, destabilised by a mountain spring, collapsed and ploughed into the Welsh mining village of Aberfan.

The inquiry into the disaster was scathing of the National Coal Board and its failure to manage the piles of waste safely, but no one was prosecuted for the disaster, or even demoted.

These tragedies, and others like them, became the trigger for change.

PA

PASince the 1800s, laws had been passed to try to keep people safe at work.

“What we used to do was wait for people to be killed and maimed,” explains Duncan Spencer from the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health.

“Then we would approach Parliament and say you need to write rules about this.”

Inevitably the number of laws grew until the early 1960s, when – in a bid for simplification – the government passed two big acts to consolidate all the smaller ones.

“Everyone breathed a sigh of relief and thought that was that,” says Mr Spencer.

But it wasn’t. For one thing, some businesses were having to abide by rules that were completely inappropriate.

Toy manufacturers were bound by the same laws as dirty and more dangerous industrial sites for example.

For another, the rules didn’t cover anticipated or potential risks.

In the case of Aberfan, there was no rule to stop the National Coal Board placing a massive and unstable coal waste tip above residential properties and schools.

By the late 1960s, it was clear something needed to be done.

Businesses were frustrated at having to follow inadequate laws, MPs were frustrated with constantly passing laws that failed to prevent horrendous deaths. Trade unions were angry that their members were getting killed at work.

‘Beyond satire’

In 1969, Employment Secretary Barbara Castle set up a committee to look into health and safety in the workplace.

In a decision that still shocks people to this day, the man she picked to lead the committee was Lord Robens.

Lord Robens was a former Labour minister who had campaigned for workplace health and safety and had experience of business and trade unions.

But he was also the same man who had been in charge of the National Coal Board during the Aberfan disaster, and who had been fiercely criticised by a tribunal into the disaster.

Prof Iain McLean, who has extensively researched the Aberfan disaster, has said the appointment was “beyond satire”.

Nevertheless, Lord Robens began his work and reported in 1972.

His committee advised flipping things completely on their head.

Getty

GettyInstead of making MPs responsible for writing legislation to protect workers it proposed placing responsibility on the employers.

It said the individual regulations should be ditched in favour of a simple principle – that the employer should identify what risks there were and take steps to mitigate them.

Two years later this principle was included as the key phrase in the Health and Safety at Work Act:

“It shall be the duty of every employer to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all his employees.”

The act also stated that employers had a duty to ensure (so far as is reasonably practicable) that they were not exposing not just their staff but also the general public to risks.

The bill became law on 31 July 1974 and is still in use.

In 2014, the Safety Management magazine produced a commemorative edition in which the act was described as “revolutionary” and “a Great British success”.

Mike Penning – then a government minister – said the act had done “more to protect our daily lives than any other”.

Laura Cameron, a health and safety lawyer, compared it to a “40-year-old malt whisky” that had only improved with time.

The Federation of Small Businesses, founded the same year as the act, thinks the law works well and that generally its members are clear about what they need to do.

‘The devil incarnate’

In addition, the Health and Safety Executive estimates that since the act, the number of fatal injuries has fallen by around 85%.

In 1974, there were 651 workplace deaths. In 2023, the figure was 135.

Some of this can be attributed to the decline in manufacturing and more of us working in offices, rather than factories.

But analysis by a former HSE chief statistician argues that the Robens Report and the subsequent law change can also be credited with the improvement.

So, to what extent does his role in making a law that saved lives redeem Lord Robens?

Daisy Silcock presents the Health and Safety Angels podcast, alongside Lynsey Mason.

“I can see how because of Aberfan, he is the devil incarnate,” she says.

“But what he did in that report was outstanding – it didn’t just change things in the UK, it led to changes across the world.”

Hanging baskets and conker fights

The Health and Safety at Work Etc Act is lauded by some but the concept of health and safety is also frequently the butt of jokes and the centre of media outrages – think bans on hanging baskets and conker fights.

A 2010 report suggested that the fault for such rows lay less with health and safety law and more with a growth in compensation culture.

Ms Mason says the act has its strength and weakness. The phrase “as far as reasonably practicable” is subjective – meaning it is flexible and can be adapted to different circumstances.

However, it is also vague and often grey areas aren’t clarified until a case ends up in court.

This can lead to organisations acting over-zealously due to a fear of legal action.

Joyce Davies

Joyce DaviesFor Joyce Davies, the impact of her father’s death, caused by unsafe working conditions, has lasted a lifetime.

To his day she still fears staying somewhere new, like a hotel, and will scrupulously check the fire doors and exit routes.

For a very long time, she hated fire fighters. “Whenever I saw a fire engine I used to mutter under my breath: ‘Why didn’t you save him’.”

And there is always the lingering question of “what if”.

“Life events – marriage, graduation, the birth of his grandchildren,” says Ms Davies. “When someone you love dies, you can’t help thinking what if he was still here.”

Joyce Davies

Joyce Davies