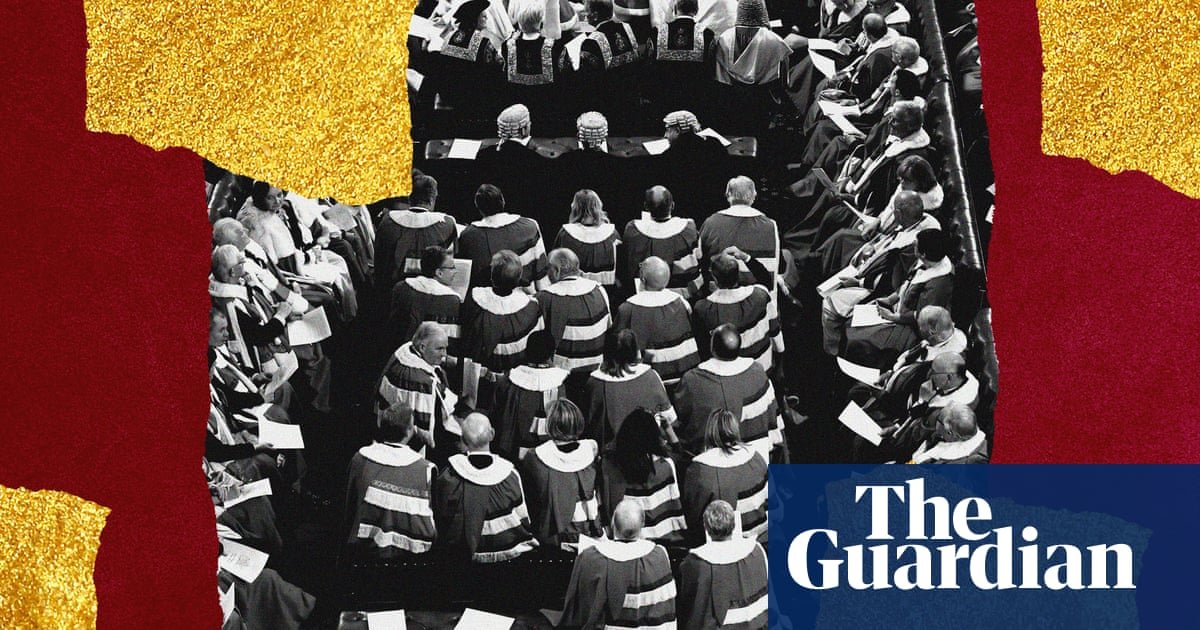

The only solid measure that Keir Starmer’s government has introduced to change the House of Lords is on its way to becoming law, but not without last-ditch resistance.

Labour’s manifesto promise to remove members of the House of Lords who vote in parliament’s second chamber by birthright was the most straightforward change. The limited measure, an overdue completion of the removal of hereditary peers that began 26 years ago, is a further illustration of the constitutional difficulties of reforming parliament’s second chamber.

Conservative peers have determinedly delayed the bill, talking up the merits of hereditary peers’ contributions to lawmaking, and putting down dozens of amendments, with alternative proposals, which have gummed up the Lords with two days of debate this week.

Nick Thomas-Symonds, the minister for the constitution, described the removal of the hereditary peers as “a landmark reform” when introducing the legislation in September. “The hereditary principle in lawmaking has lasted for too long and is out of step with modern Britain,” he said. “The second chamber plays a vital role in our constitution and people should not be voting on our laws in parliament by an accident of birth.”

But the last time Labour resolved to remove hereditary peers, when Tony Blair won the general election in 1997, the party itself was responsible for compromising; it agreed to retain 92 earls, barons and dukes. That stalled process is a cautionary tale about the obstacles to Lords reform, particularly given Labour has said in its manifesto that it has ambitious plans to ultimately replace the Lords with a modernised second chamber that represents the UK’s nations and regions.

Blair’s government capitulated in 1999 to a threat made by Tories in the Lords to block legislation if the measure was enacted without further changes. Labour then agreed the deal whereby most hereditary peers, 667, were removed, but the sub-group of 92 was retained. This was to be temporary until a second stage of promised Lords changes. That never happened. From 2010, Conservative prime ministers made clear they had no intention of changing the Lords, so 92 hereditary peers have remained in the chamber for another quarter of a century.

A process to maintain that number also persisted, despite peers in both main parties variously criticising it as a “farce” and “ludicrous”. When a sitting hereditary peer died or retired, “byelections” were held to replace them. The only candidates in the byelections were other hereditary peers in the same party who had been removed in 1999, or their children, and the only people able to vote were sitting hereditary peers from the same party as the peer being replaced.

Two of the 92 hereditary peers, who hold the ceremonial offices of earl marshal and lord great chamberlain, will remain after Starmer’s changes, but not as voting members.

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, the Marquess of Salisbury, who was the Conservative leader of the upper house in 1999, acknowledges that he secured the compromise and retention of the smaller group. He threatened to block legislation, but now says he had no intention of carrying out his threat as he believed in Lords reform. Salisbury says he argued for retaining some hereditary peers as an irritant that would encourage Blair’s government to do more, and described as “bullshit” the arguments he and colleagues used to justify the figure of 92.

“If the government had held their nerve I would have crumbled, but they didn’t,” he said. “I thought the 92 hereditary peers might last only a few more months, not 26 years.”

The Labour peer Bruce Grocott, who was a Downing Street adviser in 1999, says the government took Salisbury’s threat seriously.

“We couldn’t take the risk,” he said. “The act retaining the 92 hereditary peers was passed under duress.”

after newsletter promotion

Carwyn Jones, the former first minister of Wales, was a member of Labour’s constitutional commission, chaired by Gordon Brown, that in its 2022 report recommended replacing the Lords with a mostly elected second chamber representing the nations and regions.

“The 26 years it has taken to remove the hereditary peers, which is the right thing to do, show that such changes are never easy,” said Jones, who was made a life peer in January. “When we do decide on the longer-term reforms, we need to be resolute in taking them forward.”

The legislation to remove the final hereditary peers has nevertheless met determined resistance in the Lords. Hereditary peers have argued in debates that they are independent because they are not there by prime ministerial appointment, that many work hard, and if they are to be removed, it should be as part of wider changes.

Malcolm Sinclair, the Earl of Caithness, whose family title dates from 1455, described the legislation as a “spiteful little bill” when it was debated in December. Tory and hereditary peers then put down the bulging series of amendments that have taken up so much parliamentary time. But given the convention that the Lords does not block a government’s manifesto commitments, the bill will become law.

The general impression of hereditary peers has long been that their titles, like that of Caithness, are ancient legacies of pre-democratic times, granted by a monarch centuries ago. Many of the 92 are in this aristocratic category, including the Duke of Norfolk, currently Edward William Fitzalan-Howard, a peerage originally granted in 1312 by Edward II; and the Earl of Shrewsbury, Charles Henry John Benedict Crofton Chetwynd Chetwynd-Talbot, the 22nd holder of a title first created in 1074. But most in the Lords are not of that tradition; hereditary peerages continued to be created until 1984, when the former Conservative prime minister Harold Macmillan was ennobled as the Earl of Stockton.

David Hanson, when he was a Labour MP, was a perennial critic of hereditary peers remaining in the Lords, and singled out the 3rd Earl Attlee as “perhaps the worst example”. John Attlee sits as a Conservative, having inherited the peerage given to his grandfather Clement Attlee, a Labour prime minister whose 1945-51 government introduced the NHS and the welfare state.

“It beggars belief to think that the first Earl Attlee – a Labour prime minister who implemented some of the most dramatic reforms in Britain’s history – would have sat in the House of Lords and voted the same way as his grandson will today,” Hanson said in a 2016 speech.

Hanson lost his Commons seat in the 2019 general election, and in July last year was himself appointed to the Lords by Starmer, who made him a Home Office minister.

Attlee said he respects Hanson’s right to raise the point. Like other hereditary peers, he defended his tenure.

“Once the legislation comes into full effect, all the peers on the political benches will owe their position in parliament to knowing someone in the Westminster bubble,” he said.

Grocott acquired some renown within the Lords for speaking with a scathing wit when he repeatedly proposed bills to abolish the hereditary peer byelections, but they never passed. Now the 92 are to be removed, Grocott said: “People joke with me and ask what I’ll do with my life now this is finally happening. I have to admit to a certain satisfaction at being part of a campaign that has reached a conclusion, and has finally settled the fairly basic principle – that you can’t be a legislator by birth.”