There is a photomontage by the great British political artist Peter Kennard that cuts straight to the quick. It shows a skeleton standing to attention before a dark sea, its neck rising into a mushroom cloud. Pale vertebrae fuse with the stuttering nuclear uprush. The explosion seems to hold a face. Smoke drifts sideways like ghostly hair. There is much to say about the skill of it, but the point is to go beyond words. You cannot argue with this image.

Kennard, at 75, has long since mastered the art of the irrefutable. His montages are not just proverbial but classic. The globe as a gigantic gas mask, stuffed with warheads like sprat in a puffin’s beak. A pair of old hands trying to cut a grimy penny on a dinner plate. Constable’s Hay Wain piled high with cruise missiles, as if trundling through the English countryside to Greenham Common in the early 80s, when the work was made.

His gift is for coining the definitive image for protest movements down the decades. And just how alive and signal they remain is apparent from the free newspaper handed out at this Whitechapel retrospective. Here, old montages are readily updated in a scalpel’s cut, so that time is running through the hourglass for Gaza, as well as Syria, and spectral figures are only just visible through the flag of Ukraine. The Earth is still going up in flames in the upturned hemisphere of a military helmet, just as it was when Kennard first made the image in 1988.

The show is staged in what used to be the old Whitechapel Library, where local people came for warmth, newspapers and books. The latest installation here takes its title from the library’s colloquial name: The People’s University of the East End (2024). A thicket of Kennard’s montages appear on placards, as they so often have on London marches, but this time without added slogans. The plate of meagre coins is no longer accompanied by statistics on poverty and debt; the lorry carting a warhead down your street is no longer a CND poster. They are free to strike directly into our moment.

Montages are suspended on hanging racks, through which you can shuffle, like the day’s papers in an old library. Here is the skeleton taking an ironic interest in the government’s preposterous Protect and Survive pamphlet from 1980, and the Statue of Liberty’s torch transforming into a weapon of mass destruction. Here are Kennard’s Troops Out of Ireland campaigns, which still stagger today, with their revelations of rendition and torture.

Everything is anchored in actuality. What you see is constructed directly out of photographs – the fabric of montage – with a brilliant eye for shape and form. Look, for example, at what Kennard does with a circle. It is planet Earth, a football kicked by a US marine, a police officer’s riot shield, a clock ticking down towards environmental catastrophe or the third world war. It is a mouth, a plate, a magnifying glass to enlarge upon the world. The good old British bobby on a stamp, under such a glass, turns out to be a photograph of a real police officer wielding his baton. And circled directly below is the face of Blair Peach, fatally beaten by just such an officer during a 1979 Anti-Nazi League demonstration.

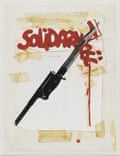

Even those not yet born by then will grasp the juxtaposition. Kennard – emeritus professor of political art at the Royal College of Art – is intent on visual clarity. You may not recognise the magnificent Solidarity logo of Poland’s trade union movement in the 1980s, but you will instantly understand the meaning of the bayonet that tries to cut the forward-flowing word in two. To the standard excuse of the world’s politicians that it is never as simple as it looks, Kennard responds with counter-arguments of irreducible simplicity.

Those old hands, for instance, are photographed directly from the life (a stunning vitrine at the Whitechapel is stuffed with all the images, gum and junk from which he conjures his images). You know them; you have seen them. The poor cannot dine upon a coin – Swiftian proposition – any more than international plutocrats can actually gamble with warheads, or small children, at the baize. Yet these photomontages partake of the very reality they expose.

And here is the crux: how would you, could you, explain this to a child – this war, this racism, this dictatorship, this vicious corporatism or deadly greed? Kennard has his old left politics; they may not be yours. Not everybody loved his montage of Tony Blair snapping himself against burning oilfields in 2005. His sporadic optimism can seem forced. The same two hands joining in a friendly shake that breaks down the Berlin Wall may appear in another montage, reaching into an incubator where a sick baby lies. The fingers are now sprouting into missiles.

But Kennard is unsurpassed when it comes to paradox, outrage and stalemate. The B-52 bomber drops an ordnance of grainsacks: modern war satirised in a nutshell. The carpet-bombing of Cambodia is reflected in Henry Kissinger’s trademark glasses. Harold Edgerton’s deathless shot of the split-second in which a bullet exits an apple – which we cannot see, but the camera can – is superbly adjusted so that the bullet is destroying a whole miniature world.

Kennard is so prolific and inventive that this archive of dissent, as he calls it, will continue to evolve at the Whitechapel until next January. His art is vital, ever- necessary. When the new Labour government starts to flag, as it may, its MPs should take a tube to the East End and be reminded that things do not only get better. There is a shocking montage here from 1982 of an elderly woman on a hospital ward where the departments are being closed down one by one. The institution is as ill as the patient. Nowadays, of course, the poor woman might not even make it out of an A&E corridor into an actual bed.