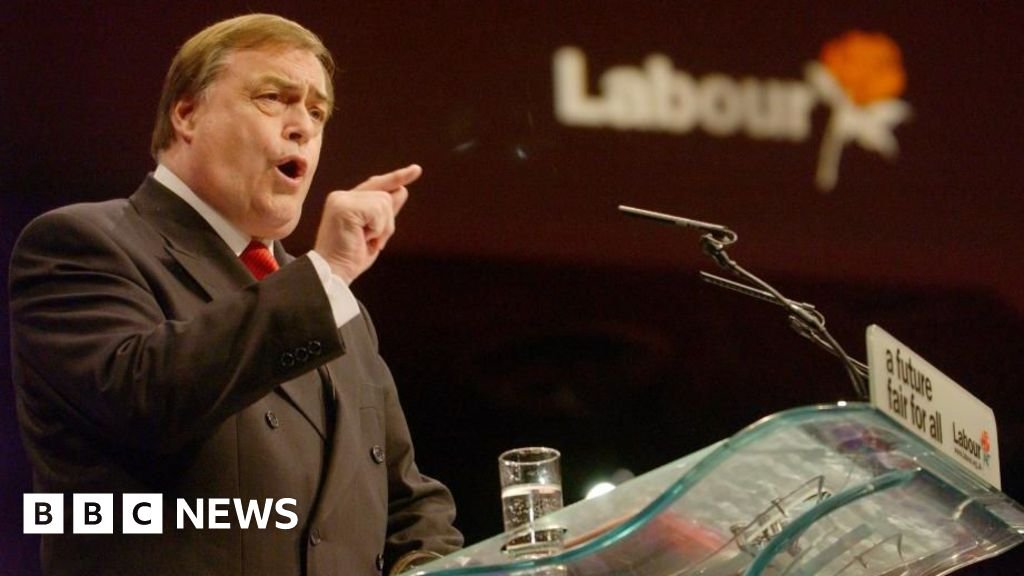

John Prescott was an old-style political bruiser who played a vital role in the New Labour project.

He scorned what he called “the beautiful people” – the men in smart suits with red roses and mobile phones who became the new face of Labour.

Yet he was an important figure in the campaign to sell modernisation to the party and pave the way for Labour to regain power after 18 years in opposition with Tony Blair’s historic landslide victory in 1997.

Towards the end of his political career, a series of embarrassments – including an affair and allegations of ministerial impropriety – threatened to tarnish his salt-of-the-earth image.

But as deputy prime minister for 10 years and part of the team that won three successive election victories, his position in Labour history is secure.

Ship’s steward

John Leslie Prescott was born in Prestatyn, Flintshire, on 31 May 1938. His father was a railway signalman and his mother came from a mining family.

Although his family left Wales when he was four, he remained proud of his heritage and always considered himself Welsh.

Rex Features

Rex FeaturesHe became a trainee chef on leaving school at 15 and then worked for eight years as a ship’s steward on passenger liners, becoming active in the National Union of Seamen.

In 1962, he went to Ruskin College, Oxford, where he got a diploma in economics and politics, and later to Hull University to study for an economics degree.

Active in the merchant sailors’ strike of 1966, he served as an official with the National Union of Seamen for two years before his election, in 1970, as MP for Hull East, sponsored by the union.

Cherished principles

John Prescott became a Labour frontbench spokesman in May 1979 and joined the shadow cabinet in 1983, gaining a reputation as a pugnacious and knowledgeable spokesman on transport.

The same year his showman’s instincts saw him swim two miles down the River Thames to highlight opposition to Margaret Thatcher’s government policy of dumping nuclear waste at sea.

But it was the Labour leader John Smith who finally gave John Prescott political room to breathe, with a key role in selling modernisation to the party and unions.

Rex Features

Rex FeaturesIt was John Smith who kick-started Labour’s slow return to power, overturning many of the party’s most cherished principles in a drive to make it electable again.

And John Prescott, with his strong union links and no-nonsense approach, offered vital support, not least in the abolition of the union block vote that had been Labour policy for years.

When Tony Blair became leader, following John Smith’s untimely death in 1994, he too recognised the importance of keeping John Prescott on board.

PA Media

PA MediaThe Hull East MP became deputy leader and later deputy prime minister with wide departmental responsibility over transport and the environment.

He pledged to create an integrated transport system and said his success would be measured by a reduction in people needing to use a car.

This caused him considerable embarrassment when, at the 1999 Labour conference, he used his ministerial car – a Jaguar – for a 200-yard journey back to his hotel.

PA Media

PA Media Rex Features

Rex FeaturesIn typical Prescott style, he claimed it was so his wife Pauline’s hair would not get blown about.

But the politician, who also owned a Jaguar himself, was soon dubbed “two Jags” in the press.

He once described himself as the guard on the Labour train – ready to slow it down if it moved off the rails. Yet his solid working-class credentials added powerful support to Tony Blair and the Labour modernisers.

He campaigned passionately against the Conservative policy of privatising Britain’s railways and was reported to have been furious when Labour failed to adopt a policy of renationalisation when returned to power.

Election punch

His policy of creating elected regional assemblies to oversee the new regional development agencies also hit the buffers, when, in a referendum in a pilot area in England’s North East, 78% of people rejected the idea.

He also faced opposition over his so-called Pathfinder project, designed to provide thousands of new homes.

As part of the policy, about 200,000 homes in the North of England were demolished, which, critics said, could have been renovated at much less cost.

Rex Features

Rex FeaturesHis passion and burly style of delivery were constant features.

He repeatedly described New Labour’s mission as delivering “traditional values in a modern setting” – a powerful if somewhat intangible concept.

Mocked by some for mangling his syntax, he often still managed to inject humour into difficult situations – such as when he was criticised for accusing a female French minister of being too tired to understand the intricacies of an environment summit.

“As to whether I am accused of being a macho man – moi?” he told the Commons. “I must say the remark leaves me most gutted.”

He hit the headlines during the 2001 general election after he was filmed throwing a punch at a member of the public who had thrown an egg at him during a protest in Rhyl, Flintshire.

John Prescott said he had acted in self-defence and police refused to take any further action. Subsequent newspaper polls suggested most people supported his reaction.

Oyster bar

In later days, John Prescott reportedly had to act as a peacemaker between Tony Blair and the Chancellor, Gordon Brown, as speculation about the succession to the leadership ebbed and flowed.

His own comment in a newspaper, that the “tectonic plates” in the Labour Party were moving, gave rise to suggestions of manoeuvring within the cabinet.

And when he was seen sharing a car with Gordon Brown and stopping off at a Scottish oyster bar, the rumours that Tony Blair was about to stand down intensified.

However, as his career as an MP neared its end, the headlines surrounding John Prescott concentrated on his private life.

In 2006, he admitted to an affair with his former secretary Tracey Temple, which led to a raft of lurid stories.

ISF PHOTOS

ISF PHOTOS Tiger Aspect

Tiger AspectIn a cabinet reshuffle soon after the revelations emerged, John Prescott was stripped of his department, although kept on as deputy prime minister and allowed to retain his salary and grace-and-favour homes.

But, in a further embarrassment, he felt compelled to give up his country pile, Dorneywood, after being pictured on its lawns playing croquet with his staff – an image at odds with his down-to-earth reputation.

It was later revealed he had visited the US ranch of businessman Philip Anschutz – whose company took over the running of the Millennium Dome and who was bidding to build Britain’s first super-casino.

Critics said there was a conflict of interest. John Prescott, who met Mr Anschutz seven times, failed to declare the visit for 11 months. He eventually said he had gone because he liked cowboy films.

The Commons Standards and Privileges Committee ruled the ministerial code had been broken because the trip had not been declared immediately.

Lording it

Shortly after Tony Blair said he would be stepping down as prime minister, John Prescott announced he would relinquish his role as deputy.

He ended his time in government with no ministerial brief of his own and was seen by many as a peripheral figure.

To the surprise of many of his supporters, he accepted a peerage in 2010 despite reportedly having once said: “I don’t want to be a member of the House of Lords. I will not accept it.”

He defended the decision because it would give him continued influence over environmental policy and he refused to treat the red benches as an upmarket retirement home, using them as a platform to carry on campaigning.

He continued to serve in the Lords until July of this year, when he was removed for non-attendance – bringing down the curtain on a parliamentary career of more than 50 years.

Rex Features

Rex FeaturesHis most robust interventions in Lords debates involved attacking the government’s response to the phone-hacking scandal.

For Lord Prescott, the matter was personal – his lawyers alleged the News of the World had placed him under surveillance, and in 2012 he won a pay out from the paper’s parent company, News International.

He was back on the stump again in 2012 when he stood as a candidate in Humberside in the elections for the new office of police and crime commissioner.

He was said to be disappointed when he lost out to a Conservative opponent on the second round of balloting.

Party loyalist

John Prescott remained a Labour loyalist at heart.

While ultimately distancing himself from Tony Blair’s decision to go to war in Iraq, he defended his former boss’ legacy and was equally supportive of the different leaders that followed him.

He also advised the then-Labour leader Ed Miliband in the run up to the 2015 election.

He was far from a natural bedfellow of Jeremy Corbyn but insisted the left-wing campaigner – who opposed nearly all of what New Labour stood for – had “proved himself”, and urged dissident MPs to support him.

His son David – who himself stood unsuccessfully for Parliament – was even part of Jeremy Corbyn’s team.

And speaking at Labour’s 2017 conference – the 51st he had attended – he said the party was on the path back to government and had a “really exciting” future.

In 2019, he suffered a stroke and was taken to Hull Royal Infirmary. But his former Labour colleague, Alan Johnson, said there were “no signs of him slowing down at all”.

To the very end, he represented a breed apart from many of his contemporaries – a Labour MP who had cut his campaigning teeth in a trades union rather than as a political adviser and who believed political principles had to be married to power.