BBC

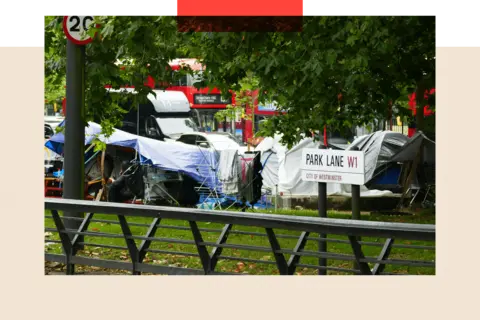

BBCOn a recent evening, on one of London’s most exclusive roads, an estate agent was selling a property for £16.5m. Outside the agency, on the other side of Park Lane, was an encampment of approximately 24 tents housing rough sleepers.

Some were sitting outside, taking in the warm night air. Others were reading by torchlight.

Rough sleeping is on the rise across England but the tents like these increasingly appearing in the country’s towns and cities are only the most visible signs of a much bigger problem.

Homelessness is, by some measures, at record levels. Over 150,000 children, for instance, are living in temporary accommodation, often miles from their schools and their friends. On occasion, some are forced to live with their entire family in one cramped, sometimes mouldy, room.

Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner says England is in the “middle of the worst housing crisis in living memory”.

To tackle this, the new government is proposing to set up a homelessness reduction unit and in its manifesto, Labour said it would “put Britain back on track to ending homelessness”.

This might sound ambitious, but homelessness is something that governments have successfully tackled previously.

Labour’s manifesto said it would meet its promises on homelessness by “building on the lessons of our past” – a reference to the Blair government’s success in dramatically cutting rough sleeping.

In 1999, Tony Blair committed to reducing the number of rough sleepers by two-thirds in three years. By 2002, his government declared it had achieved its target a year early – the number of rough sleepers in England had fallen from 1,850 to 532.

These numbers remained low for most of the remainder of the decade. The method the government uses to count rough sleeping has changed over the years but experts agree that rough sleeping fell under Labour.

In 2010, when the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition took office, the figures showed an 11-year low of 440 rough sleepers on any given night. However the then-Housing Minister Grant Shapps said he was “sceptical” that the figures reflected “the true situation on the streets” and so the counting method was revised.

Under the new methodology, the number of rough sleepers in England stood at 1,768 in 2010. After that the numbers rose, peaking in 2017. Now, the latest official figures put it at 3,898 – 120% higher than in 2010.

Even during the pandemic, when the Conservatives pursued an “Everyone In” effort to protect rough sleepers from Covid – often using hotels that couldn’t accept paying guests – the number of people sleeping outside never fell below 2,400.

The evidence of the Blair years gives Labour the confidence, however, to say it knows how to cut homelessness. But repeating the trick in 2024 may not be as easy as it was before.

And most experts believe the latest figure is a huge underestimate.

The annual snapshot, which counts the number of people found to be rough sleeping on a single night each autumn, was found by the UK Statistics Authority to fall short in “trustworthiness, quality, and value”. It doesn’t include, for instance, a person known to be a rough sleeper, but not visible on the night of the count.

And it’s not just the numbers that are greater today – the type of rough sleeper is different, too.

Alamy

AlamyThe occupants of the tents on Park Lane were mostly Romanians. Indeed in London, for which the data is most detailed and up-to-date, 55% of rough sleepers are not from the UK.

Back in the 1990s, rough sleepers in London were predominantly British and Irish. One obvious solution today would be to help those people from abroad return home.

But while such reconnecting schemes do exist, it isn’t that simple, says Matt Downie, chief executive of homeless charity Crisis. He says that some are victims of modern slavery, others have the right to remain in the UK.

“It needs untangling – they’re not all professional rough sleepers,” Mr Downie says.

Relying on the private rented sector, as councils usually do to tackle homelessness, is becoming increasingly difficult, too.

While Labour points out its commitment to ending so-called “no-fault evictions”, private rents in some areas have soared in recent years – up 9.7% in London in the year to June 2024, and 8.6% across England.

In addition, the short-term rental market, such as Airbnb, has reduced the number of properties that councils can use. London, for instance, is reportedly the city with the most Airbnb listings in the world, totalling over 150,000 – out of more than half a million across the UK.

As a result, the cost of housing families in temporary accommodation has soared. Councils spent more than £1bn on it last year, and the problem is pushing some local authorities towards bankruptcy. Several councils were forced to enter into expensive deals with the last Conservative government to cover the soaring costs of homelessness.

Treasury rules mean that Whitehall will only reimburse local authorities 90% of a figure calculated in 2011 for the cost of temporary accommodation, leading to an average monthly shortfall of about £350 per household, according to Mr Downie.

All this means the Starmer government will face a more difficult and more expensive task than its predecessor in the 1990s and 2000s.

‘Banging heads together’

There are, however, lessons the new ministers can take from the last Labour government, according to those who were there.

The key to the Blair administration’s success was getting the prime minister’s name and influence attached to the target, says Ian Brady, who was deputy director of the Rough Sleepers Unit at the time.

Tony Blair, he said, would hold regular meetings with key ministers to see what progress was being made, “banging heads together if necessary”.

There was money behind the initiative – £250m over three years – recalls Mr Brady, “a relatively big budget”. And different government departments were forced to help achieve this goal, including the Home Office and the Department of Health.

After that, a three-pronged strategy was adopted. Officials gathered data to understand who was sleeping rough. Those already in homeless accommodation, such as hostels, were moved into the private rented sector – allowing others to come off the streets. And lots of support services, such as drug and alcohol treatment, were put in place to ensure people did not become homeless again.

There are potential lessons from the Conservatives’ term in office, too.

In 2018, they funded three pilot studies of a scheme that has proven successful in tackling rough sleeping in the United States and Europe and had already been introduced in Scotland.

Housing First moves rough sleepers straight into their own properties and provides support services to help them maintain their homes. Tenancies can be kept, for instance, even if someone receives a short prison sentence or struggles to maintain contact with their drug and alcohol team.

The pilots were deemed to have been a success, with an official analysis concluding that “the vast majority of clients were in long-term accommodation a year after entering Housing First and reported significantly better outcomes across a range of measures”.

But the government has not said if it will introduce the scheme across the country, with some experts worried that it does not help enough people for the cost of the programme.

Alamy

AlamyThe Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has committed to ending rough sleeping in the city by 2030. He has not laid out the full details yet, but has promised that council house building will be a key plank – since 2018, says Mr Khan, London has built more than twice as many council homes as the rest of England combined.

Despite that, London has the biggest homelessness problem in England.

The Conservative government, in 2019, made a similar commitment to end rough sleeping by the end of the last Parliament but failed to achieve it, despite spending over £500m tackling the problem between 2022 and 2025.

In any case, rough sleeping is not the most significant homelessness issue. The latest figures from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government showed there were almost 120,000 households living in temporary accommodation – a record high – including those 150,000 children.

More than 3,200 children were living in bed and breakfast accommodation for longer than the legal limit of six weeks, a figure that is up by almost 2,000% since the last time Labour were in power.

“It’s a national disgrace,” says Ian Brady. “I wouldn’t neglect what’s happening on the streets, but I’d start by tackling that problem.”

An expert, who has the ear of the new government, said one approach would be to keep those women and children who are fleeing domestic violence in their homes and force their partners to move out by using a different policing approach.

Finding properties for those families who do end up homeless will not be easy, however.

The 1.5m homes the government has committed to building during the lifetime of this Parliament will take some time to appear, yet the homeless problem is both immediate and urgent.

In an effort to tackle the limited supply of social housing, the government is expected to hold a consultation on the future of Right to Buy, the scheme that allows council tenants to buy their homes, often at a significant discount.

Matt Downie from Crisis would go further. “I would immediately suspend Right to Buy. It’s been a disaster,” he says. Since the policy was introduced in 1980, of the almost two million homes that have been sold through Right to Buy, Shelter estimates that just 4% have been replaced.

However even if Right to Buy were to be ended entirely, some commentators say annual sales only represent a small proportion of social housing stock and further action would still be needed to tackle the shortage of social housing.

Mr Downie would also urge the government to align the allocations system for social housing in England with what happens in Scotland, so that homeless families get priority when properties become available.

One lesson that remains from the Blair years, say experts, is the need to ensure that all government departments are working towards the same aim.

The Ministry of Justice often releases prisoners into the community knowing they have nowhere to live while the Home Office has been evicting asylum seekers from their accommodation within days of giving them permission to remain in the UK, often onto the streets.

Ms Rayner has promised “a long-term strategy across Government to deal with every pressure – including increasing social and affordable housing, and providing support for refugees leaving the asylum system and prison leavers”.

Such an approach, she says, “will get us back on track towards ending homelessness for good”.

The challenge the new government faces in tackling homelessness is much greater than the last time Labour were in office. But the potential rewards are also even greater, not just in terms of saving money but in giving so many thousands of families the dignity and certainty that comes with having a place to call home.

Top picture: Alamy

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.