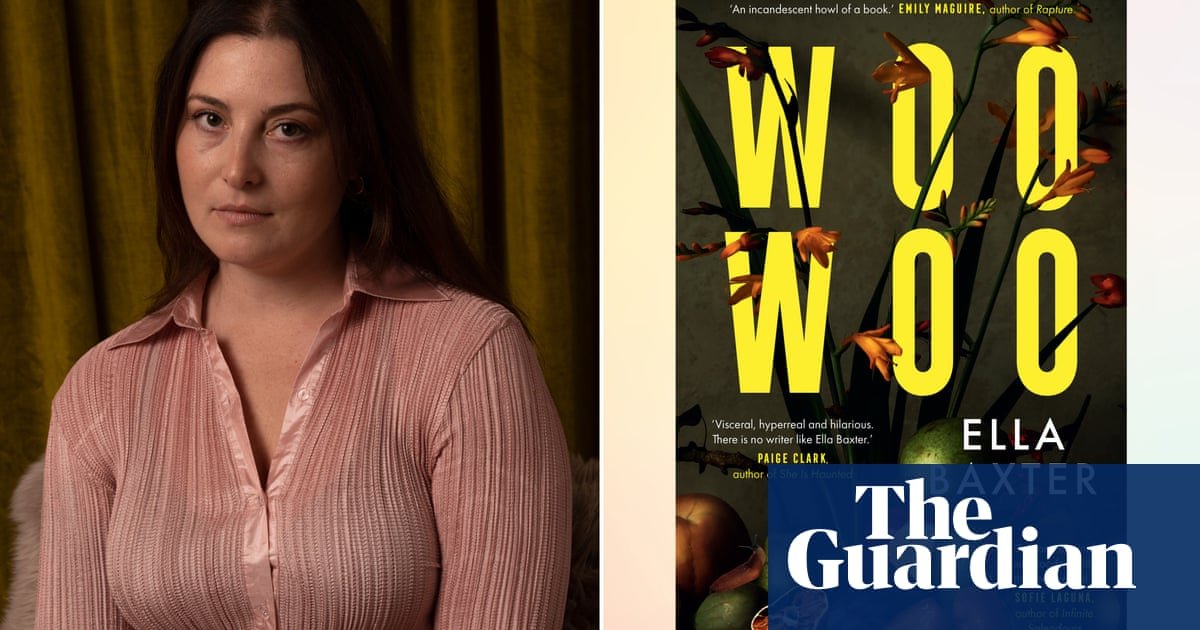

Sabine, 38 and living in Melbourne, is a reasonably successful conceptual artist. Woo Woo, Ella Baxter’s second novel, takes place the week before the opening of Sabine’s “career-defining” exhibition, titled Fuck You, Help Me. The psychic pressure of her looming public consumption is already warping Sabine’s relationships with Constantine (her chef husband), Cecily (her gallerist), and Ruth (her best friend, also an artist). Into this shimmering stress comes a stalker, whom Sabine dubs “Rembrandt man” – not a compliment.

The stalker is not a metaphor – Woo Woo, Baxter has said, is a “scorched earth response” to her own. Her novel frames art not merely as salve, but an instrument for reclaiming personal sovereignty.

No one in Sabine’s life knows how to deal with her intruder. Her social media followers think it’s a bit. Ruth is worried, but wonders if it’s “a kind of levelling up, career wise”. Constantine, disturbingly reluctant to believe it’s even happening, thinks Sabine is just spiralling. The police are believably ineffective.

Baxter’s debut, New Animal – about a grieving funeral parlour worker who stumbles into Tasmania’s BDSM scene – promised something weirder than it delivered. Woo Woo’s jagged humour feels less careful, a spiked brio that borders on slapstick as Sabine, bleached brows and silk slip, clomps around town demanding with voluptuous abjection that her nearest and dearest confirm her work is still “freakishly alluring and current”.

Because Sabine is, among many things, passionately sincere about art. (Woo Woo is lush and explicit with aesthetic influence: individual works – from Cindy Sherman, Tania Bruguera and Tracey Emin, to Eartheater, Ovid and the Kama Sutra – introduce every chapter as epigraphs.) Sabine and Constantine are happy to be finally on the up, but the “unusually moneyed” creative class around them makes Sabine uneasy. The barbed irony and “exquisite mullets” of Melbourne’s tasteful “children” spook her – like the magazine that restyles her studio to make it look more “artistic”. She keeps digging for the “skeleton of beauty in her environment”, obsessively counting the followers who join and comment while she livestreams her lunch or monologues from a toilet. It all radiates anxiety about how to be validated, and by who. Beneath Sabine’s “constant audience” lie murkier questions about exposure, vulnerability and control.

The stalker poses these questions in real time. He stands motionless outside her windows, leaves notes, “writing a role for her that [becomes] more and more horrific”. But with Sabine’s feeling of doom comes a reckless energy that overflows the bounds of regular life. In wildly surreal detours, Sabine is joined by the ghost of experimental artist Carolee Schneemann – who appears as some sort of rage doula. Schneeman pushes Sabine to break out of her fright – to consider “that artists, through their very nature, are violent”; that “scared” might be “furious”.

after newsletter promotion

Sabine listens. And finds her rage is fecund, erupting in frenzied, animal creativity. The novel’s visceral catharsis, refreshingly, doesn’t read like therapy; Baxter treats autobiographical elements (an art practice, a ramshackle rental, the stalker himself) as compost, not a garden. Woo Woo, in this sense, is a spiritual cousin to Pola Oloixarac’s superlative satire Mona: sexual, glittering, raging invention, dragged from the jaws of a would-be male predator narrative.

Sabine’s body becomes the battleground for her creative and literal autonomy. The stalker has intruded on her psyche as well as her personal space: his gaze has “become her own”. She is making art while “rotting with fear” – but then, in naming it, wrenches back agency. “My bones dislocated in fright,” she yells in one climactic performance. “My flesh abandoned me, falling from my skeleton like boiled beef, like slow-roasted lamb.” Baxter, everywhere, observes the body with carnal curiosity. Sex is a “Mariana Trench of … sweat and spit … completely aquatic.”

It doesn’t all land. Uneven sentences recall previous criticism of Baxter over-explaining “the emotional moment”. I don’t need “the night’s general lawless energy” pointed out, or that there’s “a lot to say” about art-making and cash, or for Constantine to summarise Sabine’s writhing improvisation as “feral” – or indeed the shifts to his perspective at all, which water things down.

But where New Animal was accused of being “afraid of risk”, I don’t think this can be. Its spritzy, berserk energy pulls it together like a force field. Baxter mercifully switches a too-sweet ending for an unsettling finish – but even without that, Woo Woo’s guttural, flamboyant imagination would stand it apart. As Sabine decrees somewhere along the way: “Making art is an athletic achievement.”