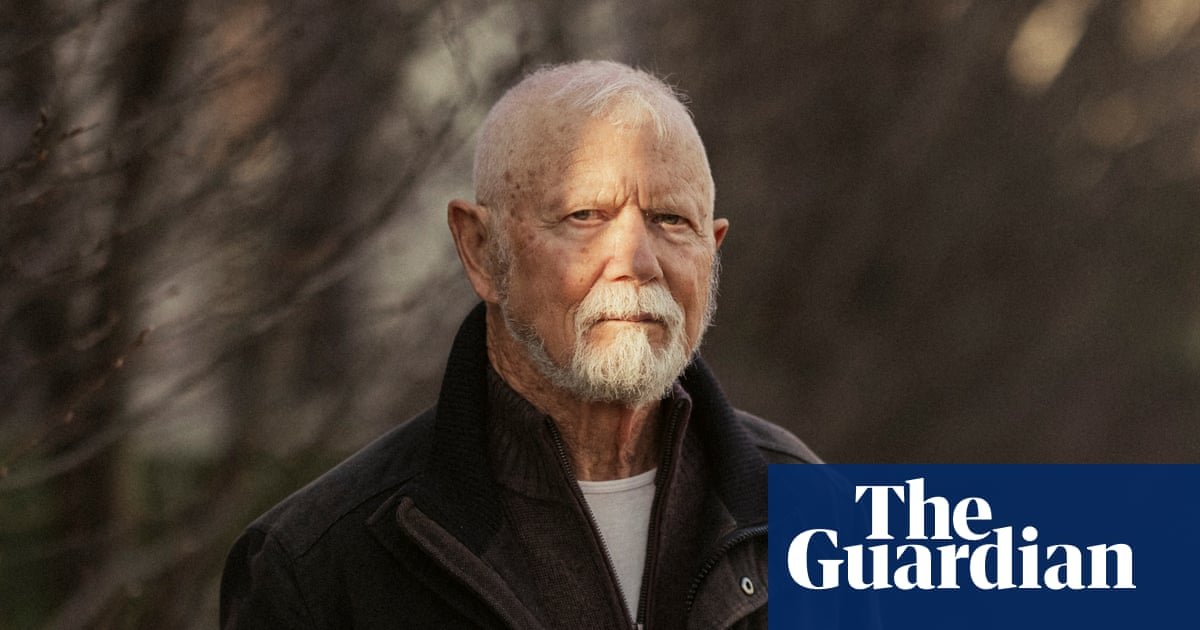

The problem with Rodney Hall – the big, insurmountable problem – is that he is too interesting. The last time I interviewed the Queensland novelist, a “quick 30-minute chat” ballooned into a whole afternoon. Hall has a polymathic heart and stories to tell.

But this time we only have an hour. No time to ask Hall about the three years he spent walking across Europe, or the role he played in harbouring Salman Rushdie in the early 90s, or the immense, multiform scope of his art-making (take a minute and Google the man). There’s a new book to talk about: Vortex – a big, ambitious book.

Hall is 88 and Vortex is his 14th novel. It may be his best, and the author has already won the Miles Franklin – twice (first in 1982 for Just Relations and then again in 1994 for The Grisly Wife). That’s more than enough to keep us occupied. But five minutes into our Zoom call and we are already on 18th-century Neapolitan philosophers.

“Have you ever come across Giambattista Vico?” Hall asks. “Vico was a colossal influence on me. He said that to understand history, you need to think of it like a sausage; you take a thin slice and inspect the inner workings. What Vico didn’t say is that you should then go on to eat the sausage.” Hall chuckles. “But that’s what I would say.” And that’s precisely what he has done in Vortex: carve off a single year and chew on it.

Hall’s year of choice is 1954: the year of the Petrov affair, the Hague Convention, Nasser’s takeover of Egypt, the transfer of Crimea, the first H-bomb tests in the Pacific, the escalation of the Mau Mau rebellion, and the early rumblings of the Vietnam war. It’s a year that sees the US mired in McCarthyism, Australia mired in Menzies, and the dawn of the New Elizabethan age. And Hall’s novel captures it all – the whole grand geopolitical tangle. The dark snare of empire.

Hall’s original plan for Vortex was bonkers. “I came up with the idea of a book in 101 chapters to be read in any order,” he explains; a grand rebuke of linearity (similar to BS Johnson’s cult 1969 “book in a box” The Unfortunates). Hall’s publishers were as thrilled as you’d expect. He ditched the gimmick, but salvaged the intention. “The root idea of this book is a web – a web of connection is how we experience life, not cause and effect.”

Vortex has a narrative through-line: a coming-of-age tale that echoes (but does not follow) Hall’s own experiences in postwar Brisbane. But that story emerges across dozens of fragments: different countries, voices, characters. There are vagrants, diplomats, journalists and spies; Brissie teenagers and errant countesses; even the young Queen herself – the great, white spider in the middle of the web. (“Kings and queens populate our card games and carnivals, our chessboards and banknotes, our gossip columns and mattress sizes,” Hall writes in Vortex, “so they oughtn’t to be surprised if now and again they chance on themselves as fictional characters.”)

Every fragment begins mid-sentence, like a snatched conversation. It’s up to the reader to imagine what’s come before – to conjure the missing pieces, furnish the connections. So much of Hall’s work is an invitation to participate, but here “invitation” feels too light a word – it’s more of an expectation. As the author himself describes it in the opening pages of Vortex, this is a “book we are creating together”.

The collaborative relationship between author and reader is one Hall takes seriously, a lesson he learned from CS Lewis: “Lewis once wrote that a novel only ever exists for two people,” he says. “It’s not the same for any other pair of readers because we bring our own life into assessing the truth of what we’re reading on the page. When the reader closes the book for the first time, having read the last page, that is what the novel is – the book that exists in that person’s mind.”

And so Hall and I talk about the book we have made together. We talk about the music trapped in Hall’s sentences, and the vortex of his title – that violent, churning metaphor and all it could mean. We talk about chaos and exaltation and synaesthesia and the artistic necessity of a thesaurus. And we talk about that gossamer yet vital distinction between moral fiction and moralising fiction, between provocations and polemics. “A lot of people think I’m political, but in a curious way, I don’t think I’m political at all. It’s too tidy,” Hall reflects. “Works of art don’t have to have political agendas, they have to survive political agendas.”

It’s a big, generous conversation. The product of a big, generous book. Sadly – shamefully – Vortex is likely to be the only one of Hall’s books you’ll find in bookstores. The rest are largely out of print. That’s a particularly cruel fate for a writer who has spent his career making space for readers, and for thorny necessary questions about the Australian project.

I want to ask Hall about the career-long story he has been weaving, and his impish sense of satire. And about what he might want to make next, as he heads into his 90s. But instead, he is telling me about the first time he ate an orange – an English wartime miracle (Hall emigrated to Australia in 1949) – and the memory is so entirely alive, I can almost feel the weight of the fruit in my hands (“It’s still with me,” Hall says, “that a fruit could be so beautiful”). It would be a sacrilege to interrupt him. And then – just like that – our precious hour is up.