For many first-time voters of my generation, the 1983 Australian federal election remains the first seminal moment of political consciousness: the contest when the workers’ Messiah, Bob Hawke, inevitably won the prime ministership he seemed destined for.

Hawke, elected Labor leader the very day Liberal prime minister Malcolm Fraser called that election, ascended with an aura of fate and celebrity, the likes of which Australian politics had not seen. The other thing about Hawke – the son of a couple who can only be described as religious fanatics, a Rhodes scholar, and a legally trained and brilliant advocate who ushered the Australian Council of Trade Unions into immensely powerful modernity – was the public sense that, for all his personal failings, he was an open book.

Blanche d’Alpuget’s Robert J Hawke (the first “warts and all” take on Hawke) was a remarkable exposé of a man gunning to be PM. So much so that today, it almost certainly would have derailed his ambition; conversely, at the time, it only seemed to help as an exercise in open-book inoculation.

His alcoholism, the boorishness, his women – so very many – became intrinsic to Hawke’s public story as he won fame as the workers’ hero, finally entered federal parliament and achieved what he and his parents had long regarded his destiny. There was a type of secular fervour attached to Hawke’s ascendancy such that his sworn sobriety and supposed – or at least publicly apparent – newfound marital fidelity was interpreted as a redemptive personal sacrifice so that the nation might finally be gifted his prime ministership.

And when it was all over, once Paul Keating had risen just as inevitably to oust Hawke (Labor’s longest-serving prime minister) in 1991, we learned even more about Hawke courtesy of his own memoir, that of his first wife, Hazel, and an updated version of the 1982 book by d’Alpuget (who became his second wife).

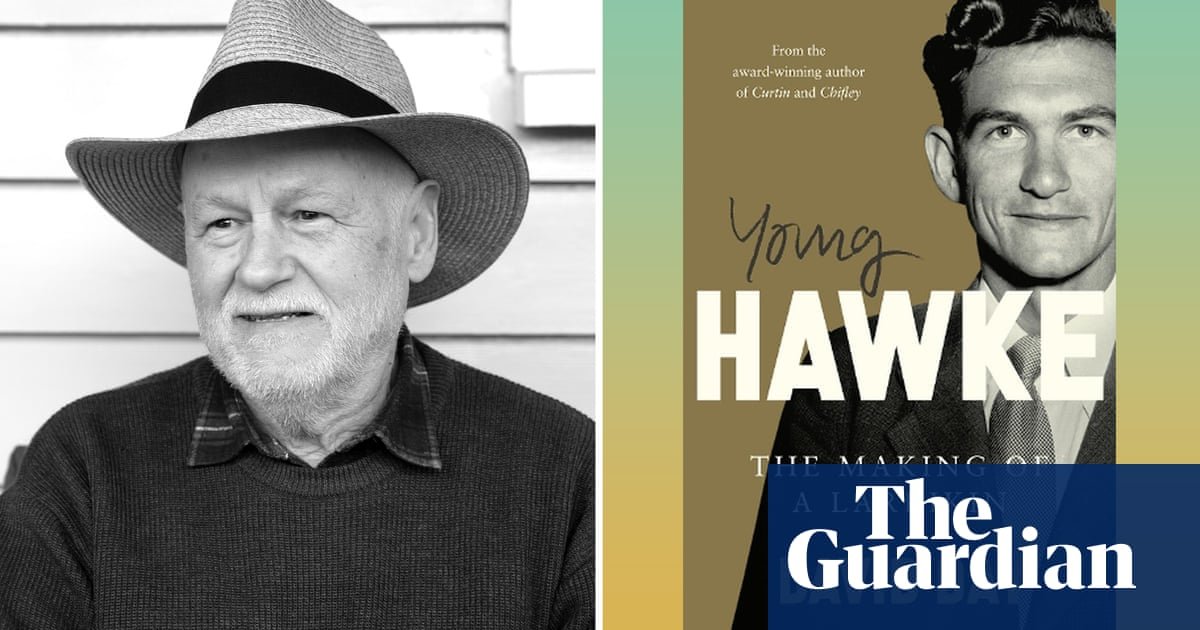

But the Labor historian David Day’s Young Hawke adds a gritty and sometimes disturbing dimension to the Hawke story. As I read Day’s book – which traces Hawke from his parental “origins” to 1979, his last year as ACTU president (another volume will examine Hawke the parliamentarian and prime minister) – I was reminded of the questions we sometimes ask ourselves about public figures, like: can we love the art but dislike the artist? In the case of Hawke, in light of Day’s book, the question for me is: can we separate the man’s amazing gains and advocacy for Australian workers, his impressive talent for consensus and his totemic achievements as prime minister, from the pathological self-regarding man?

Misty-eyed fans may not find this a pretty read. But the roots of Hawke’s purported and frequently asserted narcissism are carefully examined. There was the early death of his elder brother, Neil, in whom their parents, preacher Clem and devoutly religious Ellie (both fiercely abstemious warriors against licentiousness), had invested all hopes and dreams and against whom the young Hawke never quite measured up. That Ellie wished and prayed “Bobbie” would be born a girl and openly lamented he wasn’t exacerbated, Day contends, Hawke’s lifelong addiction to affection and adulation.

While Hawke often spoke about his intense love for his parents, Bobbie emerges as a neglected child. He was left in the care of a lodger for long periods while his parents saved souls. Clem, particularly, emerges as erratic, unstable and deeply melancholic. In Young Hawke, however, the confusing flipside to this neglect was the sense of destiny the parents imbued in the son and the unerring self-belief that propelled him to the prime ministership. Ellie, Day writes, “never tired of telling whomever would listen that Bob was destined one day to be prime minister. The young man had even begun to predict it himself.”

Australia has long known, and perhaps accepted, Hawke as a womaniser. But there is much in this book about Hawke’s treatment of women that is deeply disturbing, even repellent. For example, when the young industrial advocate arrived at the ACTU with a reputation as a hard-drinking philanderer, a senior “ordered modesty boards for the front of the desks of the three female staff members, so the lascivious newcomer couldn’t eye off their legs”, while instructing “that none of the young women were to be alone with Hawke when he moved to an upstairs office or worked there on the weekend”.

after newsletter promotion

While at the Australian National University (he studied there for a time from 1956, soon after marrying Hazel), some of his behaviour is portrayed as intensely sleazy and borderline predatory. Day recounts an anecdote about how Hawke, during “a drunken spree” with friends at a residential building, “was caught trying to climb up to a small window above the door of a terrified female student, ‘who was in bed on the other side of the door’”.

Those around Hawke, in Day’s book at least, seemed to ultimately forgive him as much as he forgave himself. During his time as Rhodes scholar at Oxford University, he urged his then fiance, Hazel, to join him from Australia as he’d been “thrust into an environment which is full of opportunities for the satisfaction of my varied tastes to which if I succumbed in their entireties, would only succeed in taking me away from you”. She eventually joined him. But she could never save him from himself.

Today Hawke’s past – his character – would probably have derailed his ambition to be prime minister. In Day’s portrait of the young Hawke, the subject emerges as self-aware about his own poor behaviour and how it hurt others. But “he was not about to change”, Day writes: “After all, his narcissism and his upbringing had convinced him that he was no mere mortal and subject to normal strictures.”

That so many others apparently believed the same allowed him to become one of the greatest prime ministers Australia has ever seen.